International Day for People of African Descent: The World Owes Us—And It’s Time to Pay Up

Bottom line up front…

Global Wealth Built on Black Labor: The piece highlights how the wealth of nations across Africa, the Americas, Europe, and Asia was largely built on the exploitation of African labor and resources.

Systemic Discrimination's Lasting Impact: It discusses the enduring effects of systemic discrimination, including policies that excluded Black people from economic opportunities, contributing to the persistent racial wealth gap.

Reparations Are Long Overdue: The piece argues that reparations for the exploitation and injustices faced by Black people are not just necessary but long overdue, drawing comparisons with other historical reparations.

Cultural Contributions Despite Oppression: Despite centuries of exploitation, the global influence of Black culture, innovation, and resilience remains undeniable, shaping modern culture, science, and social movements.

A Call to Action for Justice and Equality: The post ends with a call to action, urging the world to recognize its debt to people of African descent and to take meaningful steps toward justice, equality, and reparations.

_________________________________________________________________________________

This Saturday marks the third annual commemoration of the International Day for People of African Descent—a day that demands global reflection on the debt owed to Black people. This debt, accumulated over centuries of exploitation, remains unpaid. Every region of the world has profited from Africa and its people, and it’s time we connect the dots, expose the magnitude of this exploitation, and demand the long-overdue recognition and reparations.

Africa: The Cradle of Wealth and Exploitation

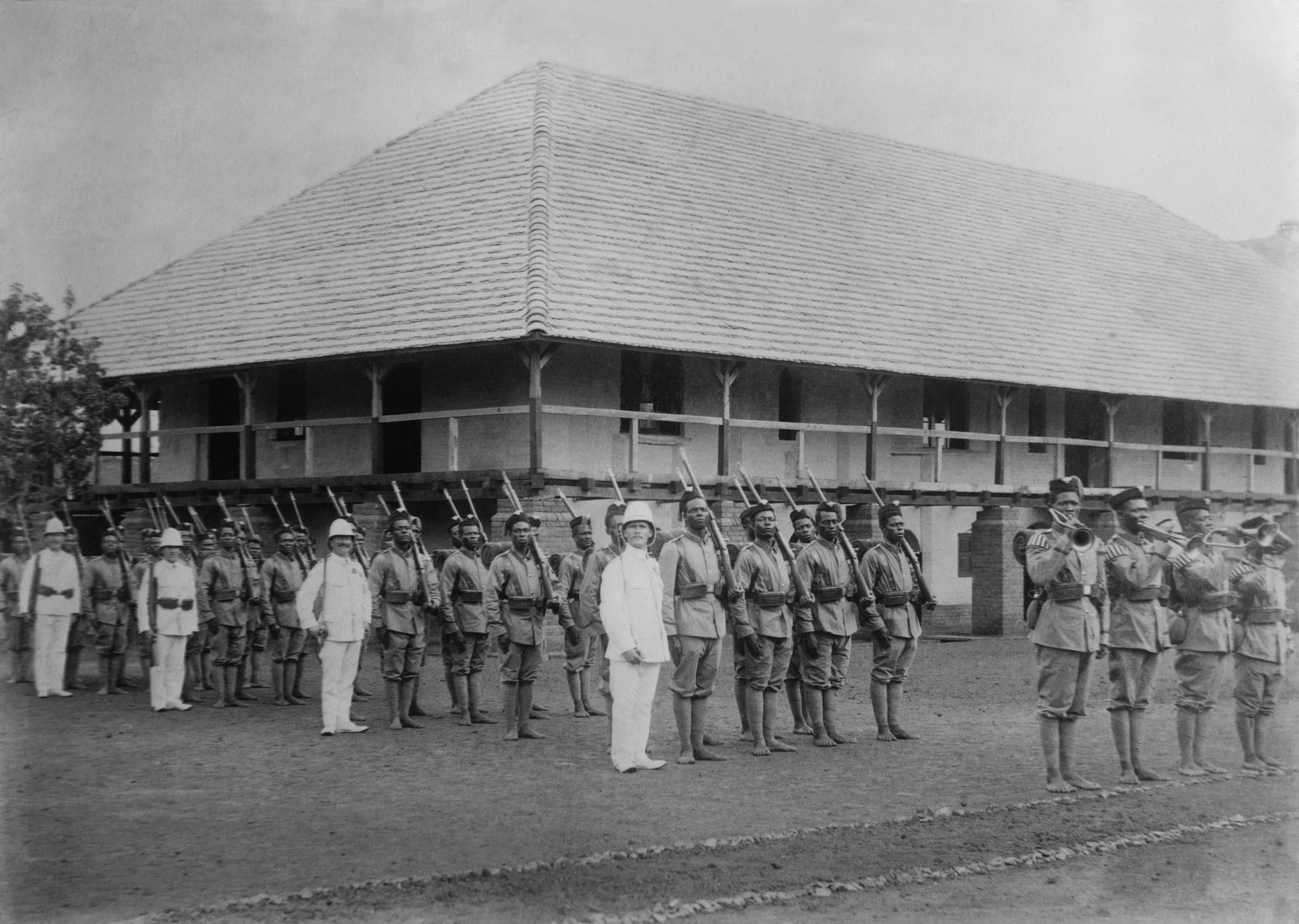

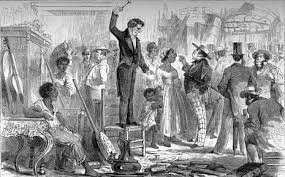

Africa, the cradle of civilization, was among the first targets of European colonization. From the 15th century onward, European powers systematically pillaged the continent, exploiting both its natural and human resources. The transatlantic slave trade, which forcibly removed millions of Africans from their homeland, was one of the most grotesque yet profitable enterprises in history.

Consider the De Beers diamond company, founded by Cecil Rhodes in 1888. De Beers dominated the global diamond market, amassing enormous wealth from diamonds extracted from African soil by laborers subjected to brutal conditions. This wealth not only enriched De Beers but also fueled the expansion of the British Empire and played a crucial role in shaping the modern global economy.

Similarly, the British South Africa Company (BSAC), also established by Rhodes, extracted massive profits from African lands and people, particularly in what are now Zimbabwe and Zambia. The resources stolen from these regions were funneled back to Britain, contributing to its industrial and financial dominance.

The exploitation of Africa extended beyond companies like De Beers and BSAC. As Eric Williams highlights in "Capitalism and Slavery," the transatlantic slave trade was central to the development of modern capitalism. The profits from slavery were reinvested into European industries, fueling the Industrial Revolution and laying the groundwork for today’s global economic systems.

South America: Empires Built on Black Labor

In South America, the exploitation of Black people was equally pervasive and profitable. Brazil, which imported the most enslaved Africans in the Americas, relied heavily on forced labor to power its sugar and coffee industries—the backbone of its colonial economy. The wealth generated from these plantations enriched the Portuguese crown, as well as European and American merchants who traded in Brazilian goods.

Banco do Brasil, one of South America’s oldest and largest banks, financed the economic activities that sustained slavery in Brazil well into the late 19th century. This financial giant directly benefited from the labor of enslaved Africans, whose forced work produced the commodities that built Brazil’s economy.

In the Caribbean, another hotspot of sugar production, enslaved Africans were the driving force behind the wealth generated by European colonial powers. Plantations in Jamaica, Barbados, and other islands produced sugar sold in European markets, generating vast profits for companies like Tate & Lyle, a British multinational rooted in the sugar trade. The wealth amassed by such companies contributed to the industrialization of Britain and laid the foundation for its global economic influence.

The United States: An Empire Built on Enslaved Labor

The United States’ legacy of slavery is evident to anyone willing to look. The Southern economy—and, by extension, the entire nation—was built on the backs of enslaved Africans who toiled in cotton fields, tobacco plantations, and sugar mills. Cotton, known as “white gold,” was the primary U.S. export in the 19th century and pivotal in establishing the country as a global economic power.

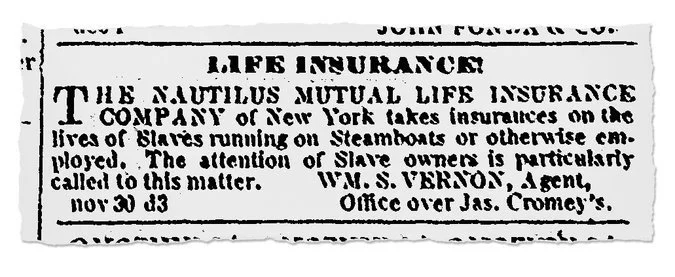

New York Life, a major American insurance company, once insured enslaved people as property, securing the wealth of slaveholders and fueling its own growth into a financial powerhouse. Profits from these policies were reinvested in Northern industries, further entrenching the economic disparities between Black and White Americans.

Northern industries also profited immensely from slavery, despite the misconception that the North was purely abolitionist. Banks, insurance companies, and textile mills in states like New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island were deeply involved in the slave economy. Aetna, one of America’s largest insurance companies, sold policies insuring slaveholders against the loss of human property. The textile mills of New England relied heavily on Southern cotton, woven into cloth sold domestically and internationally, creating vast fortunes for Northern industrialists who ignored the human cost of their wealth.

One particularly stark example is Georgetown University, a prestigious Jesuit institution that directly benefited from the sale of 272 enslaved people in 1838. The $115,000 generated by this sale (equivalent to about $3.3 million today) played a crucial role in stabilizing the university’s finances. Today, Georgetown continues to benefit from the wealth and reputation built on this horrific transaction—a reminder of how deeply entrenched slavery’s legacy is in American institutions.

Systemic Discrimination and Economic Setbacks

While the economic benefits of slavery were vast, the systemic discrimination faced by Black people in America has been equally profound. After the Civil War, formerly enslaved people were denied the 40 acres and a mule they were promised, left without land, resources, or compensation. This exclusion from land ownership was compounded by discriminatory policies like the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted 270 million acres of land to white Americans while systematically excluding Black people.

Throughout the 20th century, Black Americans continued to be left behind by federal and state programs designed to uplift the poor and middle class. The GI Bill, which provided education, housing, and business loans to veterans, disproportionately excluded Black veterans due to local administration of the benefits. Similarly, the New Deal and Social Security programs, which lifted millions of Americans out of poverty, were structured to exclude agricultural and domestic workers—the majority of whom were Black. Additionally, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) implemented discriminatory lending practices that denied Black families access to the subsidized housing loans instrumental in building wealth for white Americans. These practices, combined with land theft through eminent domain, further entrenched the racial wealth gap.

The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is another devastating example of how Black wealth was systematically destroyed. The thriving Black community of Greenwood, known as "Black Wall Street," was burned to the ground by white mobs, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of Black residents and the destruction of their businesses, homes, and wealth. No reparations were ever paid to the survivors or their descendants.

In contrast, Germany has taken significant steps to compensate Holocaust victims. From 1945 to 2018, the German government paid nearly $87 billion in compensation to Holocaust victims and their heirs. In 2024 alone, Germany will pay more than $1.4 billion to Holocaust survivors. This stark contrast highlights the ongoing failure of the United States and other nations to compensate the descendants of enslaved Africans. The lack of reparations and remedial land redistribution has played a significant role in today’s racial wealth gap, perpetuating poverty and inequality across generations.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. powerfully stated, “When we come to Washington, we’re coming to get our check.” It’s time for the United States and the rest of the world to cut the check to people of African descent globally. The debt is long overdue, and the time for justice is now.

Europe: The Industrial Powerhouse Built on African Labor

Europe’s transformation into an industrial and financial powerhouse was fueled by wealth generated from the exploitation of African labor. The transatlantic slave trade was central to this transformation, with millions of Africans forcibly transported to the Americas to work in plantations, mines, and other labor-intensive industries. Their labor laid the foundation for Europe’s industrial revolution.

The Bank of England, one of the world’s most influential financial institutions, has deep ties to the transatlantic slave trade. Many of its early shareholders and directors were heavily involved in financing the slave trade, reaping enormous profits from the human misery it caused. These profits were then reinvested into Britain’s burgeoning industries, accelerating its economic growth and establishing its dominance on the global stage.

Lloyd’s of London, another pillar of the British financial system, also has roots in the slave trade. Lloyd’s began as a coffee house where merchants and shipowners gathered to insure their ships and cargoes—many of which were involved in the transatlantic slave trade. The insurance policies sold by Lloyd’s ensured that even if a ship carrying enslaved Africans was lost at sea, investors still made a profit. The wealth generated from these policies helped Lloyd’s grow into one of the world’s largest insurance markets.

Asia: The Ripple Effects of Colonial Wealth

While Asia did not directly participate in the transatlantic slave trade, the continent was profoundly affected by the wealth it generated. European colonial powers used the immense profits from Africa’s exploitation to expand their empires in Asia, leading to centuries of economic dominance and exploitation.

HSBC, one of the world’s largest banks, was founded in the British colony of Hong Kong in 1865 to facilitate trade between Europe and Asia. The capital that fueled HSBC’s growth can be traced back to wealth generated by the British Empire, much of which was derived from the exploitation of African labor and resources. The bank played a crucial role in financing British colonial enterprises in Asia, further entrenching the economic disparities created by colonialism.

The Legacy of Exploitation

Today, the legacy of this global exploitation is starkly visible in the racial and economic inequalities that persist worldwide. The wealth that Black people created, often under the most inhumane conditions, is now on full display in the form of multimillion-dollar corporations, Wall Street, and the economies of entire nations. Yet, Black communities around the world continue to struggle with poverty, underfunded schools, inadequate healthcare, and systemic violence.

Our Global Influence: Black Culture, Innovation, and Resilience

Despite centuries of exploitation, the influence of Africans and people of African descent on global culture is undeniable. From the music that shapes global trends to the art that fills galleries, Black culture has become the heartbeat of the world. Jazz, blues, hip-hop, reggae, and countless other genres have not only defined cultural movements but also inspired social justice and change.

Our contributions extend beyond culture; we’ve been at the forefront of innovation, science, and politics. For instance, George Washington Carver’s agricultural innovations revolutionized farming in the United States, while African-American scientists and mathematicians like Katherine Johnson and Dr. Charles Drew have made pivotal advancements in science and medicine. Yet, our achievements are often appropriated or erased, leaving us to fight for the recognition and respect we deserve.

A Glimmer of Hope: Steps Toward Justice

Amid the ongoing struggle, there is a glimmer of hope. The creation of the UN Permanent Forum on People of African Descent and the UN Decade for People of African Descent are promising steps toward recognizing and addressing the historical and ongoing injustices we face. These initiatives signal a growing awareness of the need for reparations and systemic change.

The global protests following the murder of George Floyd marked a turning point, as millions of people around the world took to the streets to demand justice. For the first time, many White people began to truly understand the pervasive nature of systemic racism. This growing awareness, though slow, signals a shift in the right direction, with more individuals and institutions acknowledging the need to address the deep-rooted inequities that continue to affect Black people worldwide.

Demanding What Is Rightfully Ours

As we observe the International Day for People of African Descent, we must remember that the world owes us. It owes us for the centuries of stolen labor, land, and lives. It owes us for the wealth it built on our backs. But most importantly, it owes us respect, justice, and equality.

The fight is far from over, but cracks are appearing in the walls of systemic racism. We must continue to push forward, demand what is rightfully ours, and build a world where future generations of Black people can thrive. The world may owe us, but we are the ones who will define our future.

Let this day be a reminder that we are not just survivors of history—we are the architects of tomorrow.

TL;DR: It’s time to cut the check!